Cory's Cookies and The 92% Tax Rate

John David Pressman

Marginal Revolution recently did a post on CNBC’s The Profit. The Profit is a reality TV show where the host, experienced managerial talent Marcus Lemonis, buys into a struggling small business and uses his management expertise to bring it back into profitability. Out of curiosity I decided to watch a few episodes myself on YouTube. Of the full length episodes available on CNBC’s channel, the one featuring Mr. Cory’s Cookies really stood out to me. In many ways this episode is the perfect representation of the series core themes. Cory’s Cookies is being run by Cory, who is 13 and wants to be a big businessman when he grows up, and his mother Lisa who is by her own admission an uneducated person learned of little but the school of hard knocks. The overall thrust of the episode is that Marcus invests $100,000 into the company, and then builds the family business a real supply chain. The entire episode is fascinating, and I really think that it’s worth your time to give it a watch. However this post is not a review of the episode itself, but rather an exploration of something interesting that’s highlighted within it.

At 17 minutes and 32 seconds into the episode, Marcus sits down with a copacker that Lisa has done a licensing deal with. He’s frustrated to learn that the copacker has managed to get Lisa to sign a 8% royalty deal giving them all retail rights to the Cory’s Cookies brand. As Marcus puts it, a million dollars made from retail sales translates into $80,000 for Cory’s Cookies. This on its own isn’t particularly interesting, on the surface it would just be a predatory licensing deal. What’s interesting is that when Marcus calls the copacker out on this, they reply that 8% is a standard industry royalty. And Marcus doesn’t particularly object, which leads me to believe that’s probably true. When I heard this it blew my mind, it’s an implicit commentary on the value of a business that gives us a platform from which to deconstruct the notion of a “business idea”.

So What Goes Into A Good Business Idea, Anyway?

Here’s a conversation you may have had with a friend before:

YOU: Man, I really want to do a business or something.

FRIEND: Well you could sell lemonade. :P

YOU (thinking to yourself): Thanks for taking this seriously, jackass.

There’s an intuitive level on which you understand “sell lemonade” or “sell cookies” is a bad plan of action for starting a business. Yet Kraft makes millions doing just that so what’s the difference? Is it just capital? Well, no. I’m willing to bet if I dropped 15 million dollars into my average readers lap with the stipulation that they use it to make a kickass lemonade brand their success would be far from consistent. Traditionally economists identify three major resources necessary for business:

- Land

- Labor

- Capital

More recent business texts add a fourth necessary resource that goes by several different names. Generally this is some form of managerial talent or risk taker willing to try a new enterprise. Attitudes toward this range from “that’s dumb” to “this is essential and we’re stupid for not including it earlier”. I started out in the first camp but now find myself firmly in the second. To explain why, it’s illustrative to take a trip back to Mr. Cory’s Cookies and look at exactly what it is Marcus is doing to help their business. Right away Marcus takes note of the fact that the copacker deal only applies to retail, and focuses on making a kickass direct to consumer supply chain. A major problem in doing this is that the cookies are not made with preservatives so their shelf life is absurdly short. Because of this the original copacker Lisa tried to bring the cookies to market with couldn’t replicate Cory’s recipe in a useful way. To make it happen Marcus employs:

- Rastelli Global, a shipping company that can work around the fact that Cory’s Cookies have a painfully short two day shelf life using flash freezing technology.

- Century Packaging, a printer that can get Cory’s Cookies a proper container to put their cookies in for Rastelli to ship.

- A copacker that is only handling the manufacture of cookies, not other aspects of the business like the one Lisa signed a licensing agreement with. As a consequence, they’re getting paid on contract to make cookies, not run the whole supply chain. This leaves a lot more profit margin for Cory’s Cookies to take advantage of.

It’s important to note that these are not random companies, at the very least Rastelli Global and Century Packaging seem to be companies that Marcus has already worked with in the past. Critically, he knows they’ll get the job done at the price point he wants. This information on not just what kind of firm to employ but which ones are trustworthy, along with the necessary resources to make the transactions happen, is worth 92% of the Cory’s Cookies business. Going by the example of the copacker Lisa signed a licensing agreement with, we can conclude that not having the knowledge or relationships to make this supply chain happen incurs an effective 92% tax on revenue. It is worth stepping back for a minute to fully appreciate how subtle yet brutally costly information effects really are. Yes Marcus invested 100k into the business, but a loan from the bank for the same amount would not have gone nearly as far without Marcus on staff to put this together for them.

What’s the moral of this story? Well…

Recontextualizing The ‘Business Idea’

The problem with your friends lemonade suggestion is that it’s not actionable. This is the basic problem with the ‘idea guy’, a creature that has now thankfully been laughed out of even middlebrow portrayals of the business ecosystem. Standard wisdom says that the value of an idea is zero. I think this is only really true if you narrow down ‘business idea’ to exclusively refer to the most abstract, high level description of a field of endeavor. All the messy implementation details go into the ‘business plan’. The distinction between a ‘business idea’ and a ‘business plan’ is that a good business idea can be had by anyone, but you need managerial talent to make a good business plan. If I say:

“Hey, you should sell some lemonade” and I basically describe a roadside lemonade stand, you might be tempted to hit me.

“Hey, you should sell some lemonade” and I describe how there’s a market opportunity for someone to sell high quality commercial lemonade at 50 summer fairs and how you would make deals with them & get the supplies to make the drinks, well that’s significantly more interesting.

“Hey, you should sell some lemonade” and I describe a recipe for making a better lemonade powder than Country Time and exactly what companies you would use for supplies and how you’d get various retail stores to carry it, that’s amazing!

If I call that giant description a ‘business plan’ rather than a ‘business idea’, well then we can just shift phrasing and say that a good business plan is worth a hell of a lot. Fred Smith, the founder of FedEx, understood this well. He wrote a college paper describing a business model that would allow someone to compete with the U.S Post Office for delivery. His paper did not receive high marks, Smith looked at his grade, looked at the paper and said “No, that’s horseshit I know this will work”1. He dropped out soon after to pursue the business for real. History vindicated Fred Smith, and if I know anything about human nature that professor probably insisted till the day he died he’d been correct. The irony of this is that anyone capable of making a business plan they know will work is probably just going to pursue it themselves. Why hand someone else free money?2

There is a subtle affliction that causes one to believe their detail poor business ideas are in fact solid business plans. I like to think of this affliction as Spherical Cow Mindset. The Spherical Cow Mindset is characterized by a tendency to go mapmaking without the territory. It’s encountering problems and trying to solve them from scratch instead of studying the solutions of others. Its insisting on principles of phenomena that reside entirely in ones head. It’s building a social network for lawyers without doing a single user interview first. It is intellectual, operational cancer! And the patient is functionally brain dead until the tumor is excised by exposure to reality, or perhaps less deranged patterns of thought.

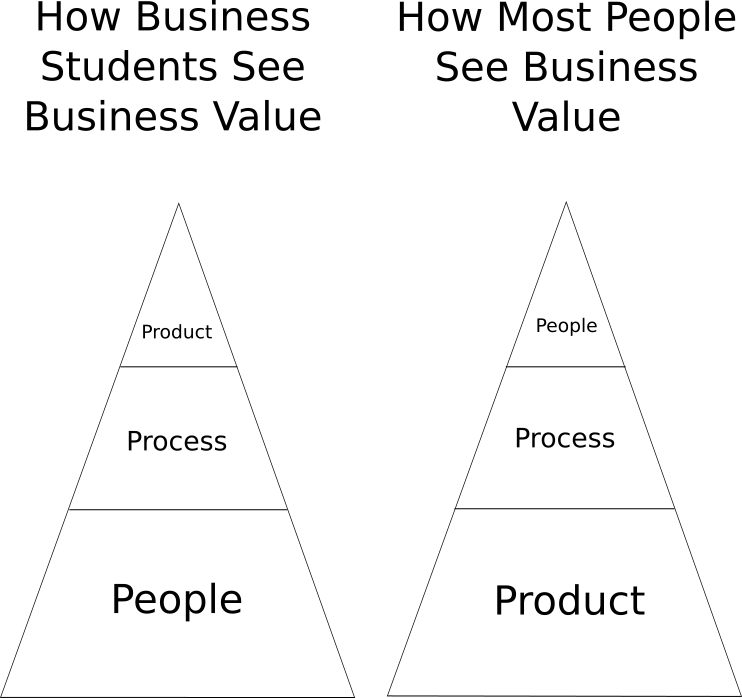

Its essence is a failure to think in systems, refusing to model reality with as many moving parts as are actually required. The truth is that most people have business value almost exactly backwards. A common mantra for new school managers is people/process/product. The average person thinks of business in terms of product/process/people. I suspect this is because when you observe the system from the outside that’s how it looks. You see the product, peer at the process, and eventually stop at the controllers behind the scenes. In this view of things you have the product, which is a platonic ideal model kept in a hermetically sealed vault in Switzerland. Having this platonic ideal is most of the value, after which a ruthless process of copying is used to distribute imitations of the product widely. This is handled by a sprawling machine that’s merely infrastructure, so it’s not as valuable as the unique contribution of the product. Finally you have managers, who occasionally hit the machinery’s cog-people with cudgels to keep them in line. The manager contributes a fraction of the value but takes a disproportionate cut of the proceeds because he’s a troll living under an unassailable bridge and no one can stop him.

Marcus Lemonis runs into this with Cory’s Cookies. Standing in a commercial kitchen he challenges Cory to name the essential numbers for the enterprise. In a discussion of labor Cory and Lisa insist their labor cost is zero because they don’t pay anyone to make the cookies. Marcus doesn’t use the words ‘opportunity cost’, but he tries to impress upon them that they’re valuable and shouldn’t think of themselves like that. For many years the popular wisdom was (and often still is) that people who found companies are not necessarily the best people to run companies. I don’t know about companies, but a common question I ask myself about anyone running anything is if they could have set things up themselves. If the answer is “no” I get real skeptical about the long term prospects of their enterprise.

-

Kiara, Robert. (2018, March 13). How FedEx’s founder revolutionized shipping with a mediocre college term paper. Retrieved from https://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/how-fedexs-founder-revolutionized-shipping-with-a-mediocre-college-term-paper/ ↩

-

One potential reason is that even a solid business requires risked capital, but then that’s what VC money is for. ↩